Similarly, the far-right, pro-Trump conspiracy theorist Alex Jones is often so over the top on his InfoWars broadcasts that his own attorney likened him to a "performance artist" during a court hearing about Jones' divorce.

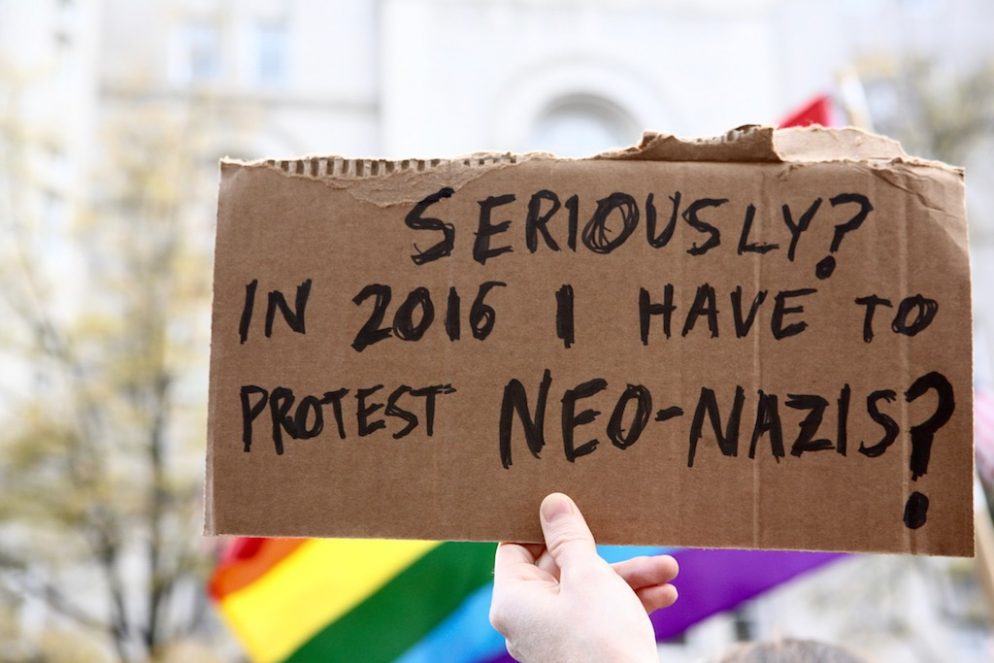

"Because if you point it out, it's, like, 'well, they're so goofy.' " "It distracts from what their actual political ideology is and from their violence," said Miller. The Proud Boys are "funny dudes, not Nazis," McInnes wrote.īut Cassie Miller of the Southern Poverty Law Center said the group's use of "jokes" is strategic. Gavin McInnes, the group's founder, said in an email that the media, including NPR, "willfully ignores" jokes to paint the group in a more negative light. In retrospect, Flood's concern does not seem like an overreaction. (As a public university, UCLA is legally bound to follow the First Amendment, which protects hate speech.)

#VOX DAY ALT RIGHT FREE#

"And, like, I really hate to say, it sounds so much like, overblown, 'snowflake,' that we're just overreacting, you know?"Īnd throughout 2020, students told NPR, UCLA took no action against Secor despite his escalating rhetoric, likely because of free speech concerns. "I definitely felt that sense of threat," Flood told NPR recently. "It's called a joke and the fact that you think that these posts are anything more than that is telling," added Secor.įlood, who is Japanese American, said they wanted to speak up. When one student called Secor out for a tweet that the student found offensive, Secor responded that he was using "post irony." Often, Secor adopted the kind of "trolling" style that's prevalent on the internet. Around that time, he was also posting racist and antisemitic memes and tweets, attacking immigrants online and publicly supporting Fuentes. The classmate, a 22-year-old named Christian Secor, was already well-known for his self-proclaimed "love" of guns. In early 2020, Oona Flood started getting more and more worried about a classmate at the University of California, Los Angeles. They can't handle it - they're sensitive babies,' " said Jared Holt, a resident fellow with the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab. "A lot of these content creators will tell the audience explicitly, 'When people say you're racist for liking this or thinking this, just laugh at them. Researchers who track domestic extremism say Fuentes is not the only figure to adopt these tactics, particularly among far-right content creators, who encourage their audiences to follow suit. "When it comes to a lot of these issues, you need a little bit of maneuverability that irony gives you," Fuentes said.Īnd, in fact, after Fuentes questioned the death toll from the Holocaust in one rant, he later claimed to The Washington Post that it was just a "lampoon." He specifically cited Holocaust denial - or what he termed Holocaust "revision" - as a topic that is too fraught to discuss earnestly, even on the far right.įar-right extremist Nick Fuentes, seen here in a screenshot from his livestreamed show, has said he uses irony because it provides "plausible deniability" and cover for some of his most incendiary statements. "Irony is so important for giving a lot of cover and plausible deniability for our views," Fuentes said in a 2020 video. Paul Gosar, R-Ariz., spoke at a political conference that Fuentes hosted, drawing widespread criticism.īut Fuentes has said himself that he uses irony and "jokes" to communicate his message without consequences. Though Fuentes exists on the fringes of the extreme right, Rep. His followers refer to themselves as "Groypers" - a reference to a mutated version of the Pepe the Frog cartoon that was co-opted by the far right. Researchers who track domestic extremism say the tactic, while not new, has helped several groups mask their danger, avoid consequences and draw younger people into their movements.įuentes is best known for using cartoonish memes to spread white supremacist propaganda. Just a joke."įuentes was following a playbook popular among domestic extremists: using irony and claims of "just joking" to spread their message, while deflecting criticism. He then added, "No, I'm kidding, of course. At one point, he pantomimed punching a woman in the face. "Why don't you give her a vicious and forceful backhanded slap with your knuckles right across her face - disrespectfully - and make it hurt?" Fuentes went on.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)